The Role of Public Art in Addressing Firearm Violence

By Jane Prophet, PhD.

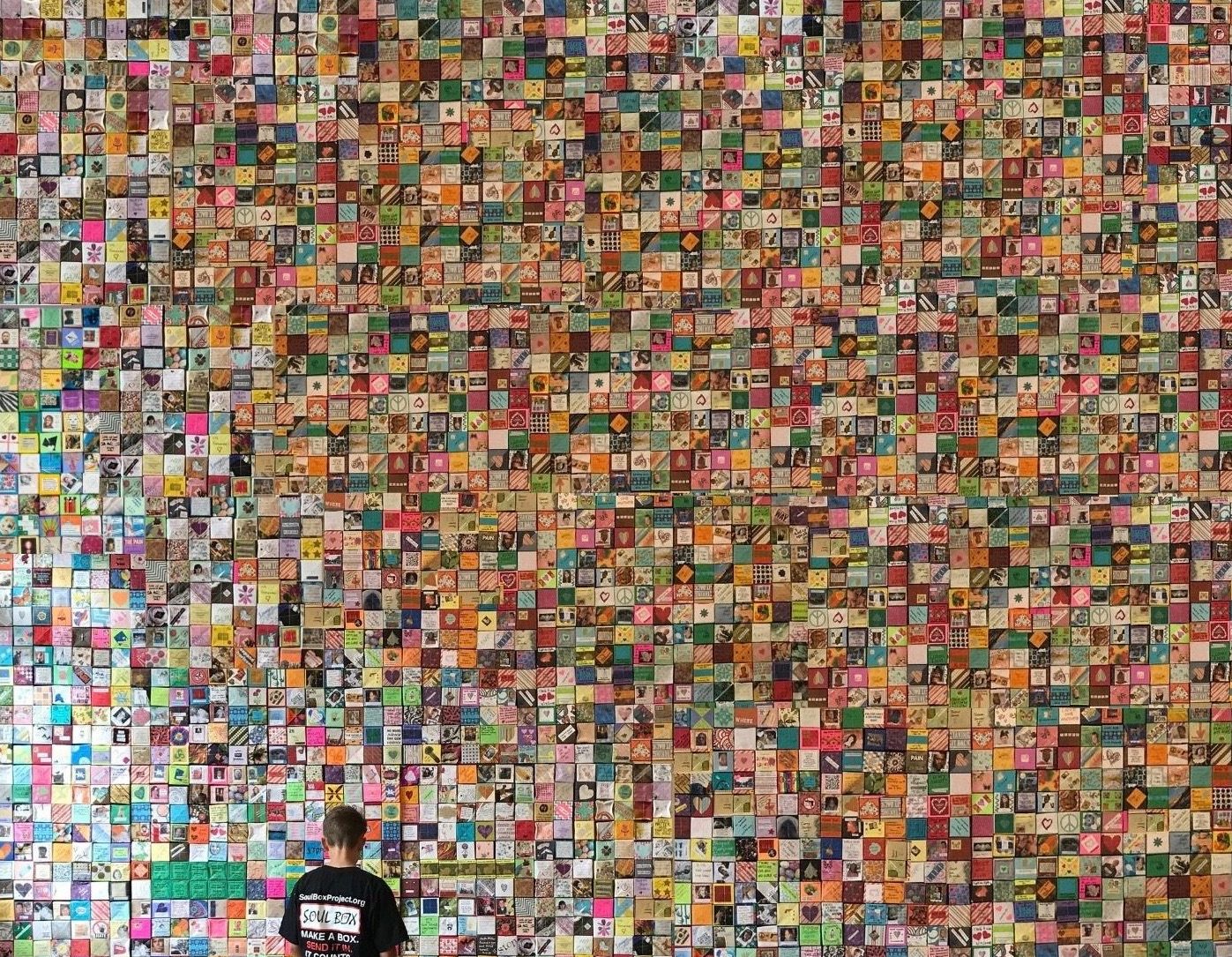

In 2019 NEA Lab PI Jane Prophet worked with Lia New (‘22 Art & Design) to find out more about US artists designers working in response to firearm injury. We found that most works were produced to implement or promote change by using art to share information and many were designed to appeal to people’s sense of justice. We were surprised that there were few examples of designed-objects, with exceptions such as Reach, a biometric handgun safe, in contrast to a more significant number of works defined as art. Many artworks had a purpose beyond aesthetic pleasure: artists and designers created the works to encourage communities to respond to various societal issues and engage visitors with that issue. The works themselves and public events associated with them were often participatory, involving people as the medium or material of the work. A significant social and public health issue that has been the focus of such artworks is firearm injury and death. One example of such artworks is The Soul Box Project, founded by Leslie Lee, where origami paper boxes commemorate each person killed or injured by firearms in the U.S. Visitors are asked to make a box and share the story of someone lost or injured to gun violence. Creatives described feeling compelled to make works, often in response to specific events, like the murder of George Floyd which prompted muralists all over the world to create images of him to express grief, outrage and in protest. Others were intended as sites and events that would bring people together after firearm injury as part of community grieving and healing, such as David Best’s Temple of Time, the ceremonial burning of a large plywood temple by families of those lost, those injured, hospital staff, first responders, and special needs people, representing those killed in, and those that survived, the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, Parkland, Florida. Although we found information suggesting works were tailored to specific communities and/or emerged from community workshops, we have limited documentation available about what happened during the workshops and what learning and sharing came out of those workshops in addition to the artworks themselves. Overall we found a lack of information about how to structure such projects, a paucity of funding to implement such projects, and little shared material about best practices for mentoring and supporting artist-community collaboration. This brief online study made us want to know more about how effective artworks are in catalyzing community engagement and healing communities. Our next step was to build a team of artists, designers and public health researchers to engage in a conversation about how public art might accelerate firearm injury prevention.